Osamu Tezuka:

The God Of Manga

It’s no exaggeration to suggest that Japan’s mammoth manga and anime industries would not exist today without the innovations of Osamu Tezuka (1928-1989).

Tezuka pioneered short story and long-form manga and constantly refined their expansive, visually oriented storytelling. He started this in children’s comics in 1947 with Shintakarajima (New Treasure Island). In 1963, he animated his Astro Boy for television, the first manga to spin off into cartoons. His example inspired generations to come. To the Japanese, Tezuka is a cultural icon, one of their nation’s most significant 20th century figures, celebrated in his own one-man museum and almost worshipped as the ‘God of Manga’.

His Astro Boy cartoons were instantly exported to America, thrilling TV viewers from 1963, and yet his comics remained unpublished there, even when the manga invasion began in 1987. Maybe his series were perceived as too cartoony, too quirky, too culturally Japanese, to cross over?

Whatever, it was not until after his death, that Viz Comics, buoyed perhaps by the success of Maus, Art Spiegelman’s Holocaust family history, took the plunge and chose Tezuka’s 1,200-page World War II adult graphic novel Adolf as his first work they would translate in 1995. Created between 1983 and 1985, this five-volume anti-war tragedy blends fact and fiction during the rise and fall of Hitler, including damning documents proving his Jewish heritage. In search of this, a Japanese reporter unravels the intertwined fates of two boys both named Adolf, one Jewish, the other half-German, half-Japanese, childhood friends in pre-War Japan.

Tezuka shows their lives trampled over by the egoism of the state, first by Nazism’s racial hatred, which brainwashes one young man into executing his Jewish friend’s father, and ultimately in a showdown on opposing sides of the Israeli-Palestinian War. As a teenager, Tezuka experienced firsthand the devastating attacks on his homeland and Japan’s war machine propaganda. These instilled a lifelong mission to speak out against all forms of discrimination and fundamentalism, in Adolf and in much of his output.

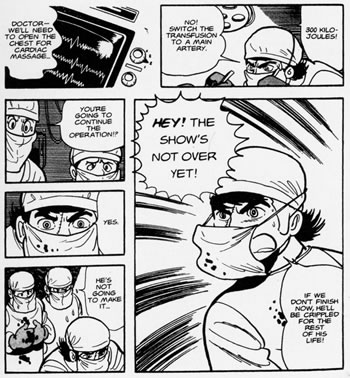

As a qualified physician, Tezuka might have become a doctor, if not for his early success in comics. He brought this knowledge into Black Jack, an unlicensed renegade surgeon, whose long black hair, streaked with white, couldn’t hide his scarred face. Although less ‘realistic’ than Adolf, most Black Jack episodes are punctuated by Tezuka’s authentic CSI-style sequences of surgery. In all, his enigmatic doctor performed 244 ‘operations’ of about 20 pages each, of which Viz published 18 in two collections in 1998-99.

Since then, no more Tezuka translations. Until recently, when Dark Horse launched a monthly series of 23 paperbacks compiling all 69 Astro Boy tales from 1951 to 1968. Forget Gold Key’s 1965 one-shot, forget Now Comics’ 1980s imitation, this is the genuine original, with his big, emotive eyes out of classic Disney and Fleischer cartoons, his red rocket boots, his machine guns in his butt, and his retro-cool world of tomorrow. Since his origin as a robot replacement for a scientist’s dead son, Astro Boy strives to become more human and reconcile relations between people and robots. Somehow, out of post-Hiroshima defeat, Tezuka visualised a future Japan that is almost real today; no wonder huge celebrations were held there for Astro’s birthday on April 7th 2003.

Tezuka considered Phoenix his ‘life’s work’, creating it from 1954 until his death. Left unfinished at over 3,000 pages, this saga’s second story, Future, from 1967-68, was released in 2003 by Viz. Tezuka transforms the immortal bird of legend into the guardian of the living cosmos, endlessly renewing itself through a history that swings between our world’s ancient dawn and its end in the 35th century. Future is almost a Buddhist science fiction parable, showing the folly of humankind’s self-destructive evolution, while we ignore the interdependence of everything, from galaxies to the tiniest particles, in a cycle of death and rebirth. It’s mind-expanding, riveting, and sees Tezuka soar to new heights.

During his forty year career, Tezuka wrote and drew a record 150,000 pages, or an average ten pages every single day (for comparison, Jack Kirby’s estimated total is 21,000 pages). Tezuka’s dying words to his wife were, "I’m begging you, let me work!" He was a visionary, who dedicated his life to advancing comics as a humanising global language. His manga were his gift to the world.

Finally, a pronunciation tip: Tezuka doesn’t rhyme with ‘baz-OO-ka’; instead, slightly stress the first syllables: OSS-a-moo TEZZ-oo-ka.

Posted: October 30, 2005The original version of this article appeared in 2003 in the pages of Comics International, the UK’s leading magazine about comics.