Milo Manara & Federico Fellini:

Stories Without End

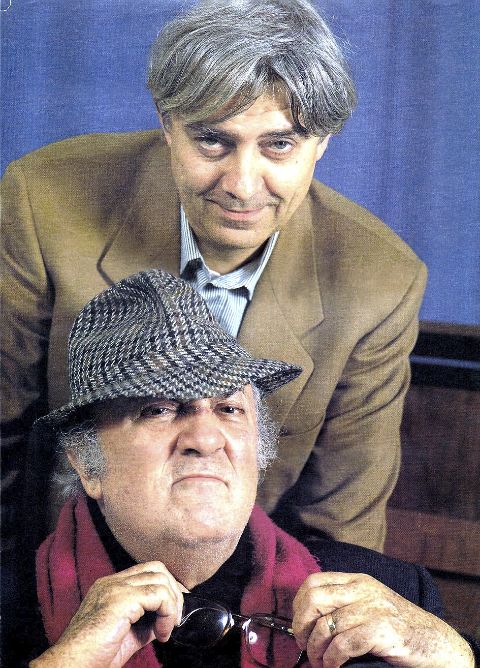

Milo Manara and Federico Fellini (1920-1993) are acclaimed worldwide as two of Italy’s greatest maestros of their respective artforms. The universal media of comics and film have often been compared, as if comics can be reduced simply to films on paper, as if sequential panels equate with the preparatory storyboards for a movie, whereas there are probably many more differences between them than similarities. What is clear is that there has been a long and continuing cross-pollination in both directions between comics and cinema and this has hugely informed and influenced both Manara and Fellini.

In composing his pages and narratives, and in various visual quotations, Manara took great inspiration from films and specifically those made by Fellini, notably in his increasingly fanciful, free-flowing graphic novel series HP and Guiseppe Bergman. His admiration for the director culminated in the creation of Untitled, a tribute comic of four dreamlike pages starring a bewildered Marcello Mastroianni in hat and toga. Manara fills it with references to Fellini films, from Casanova to the S.S. Rex ocean liner in Amarcord, and adds a nod to Nino Rota, who had died in 1979, the composer of many scores for Fellini’s movies.

Appraising what for him distinguishes Fellini from other film-makers, Manara commented in his introduction to the first American edition of Trip to Tulum (Catalan Communications, 1990, above) : “Plot, development, narrative thrills and chills have only relative importance for Fellini. What matters to him is the revelation of marvels, the awe-inspiring bringing to light of secret essences, the ineffable universal transfiguration uniting everything.” Manara’s highly personal and distinctly Fellini-esque Untitled captures these qualities and would finally bring the two men together. Manara recalls, “I first met Fellini in 1985 after he called me and told me how much he liked my short homage to him, Untitled, which I had dedicated to him. Like Hugo Pratt, Fellini was another truly extraordinary man on the human and personal level. Both were key teachers for me, for my life and my work.”

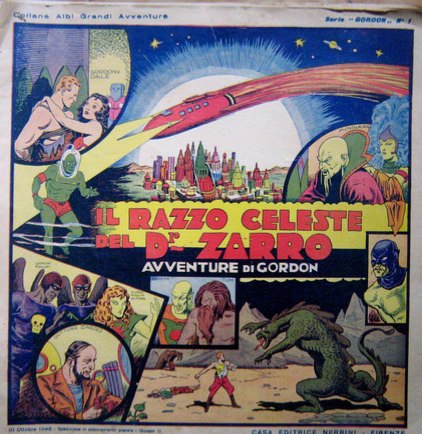

Fellini’s enthusiasm for comics, including Manara’s oeuvre, was nothing new. In his childhood in the Twenties and Thirties, little Federico had devoured Italy’s translated editions of such classic American newspaper strips as Mickey Mouse, Bringing Up Father, Tim Tyler’s Luck, Mandrake, The Phantom and Flash Gordon (above), published by Edizioni Nerbini in Florence, alongside their own homegrown Italian characters. These instilled an eagerness to draw and as a young man in the late Thirties, en route from Rimini to Rome and the Cinecittà studios, Fellini found work at Nerbini, contributing to their satirical weekly 420. Asked about his early career in a filmed interview with French critic Francis Lacassin, Fellini also recounted his contribution of scripts to Nerbini’s Flash Gordon, after Mussolini’s Fascist regime barred the importation of the American originals. “I only continued the storyline, by anticipating, from what I’d read and from what had been published up to that point, how the various episodes would be configured. I tried to imagine the continuation of this story, while Giove Toppi, an illustrator for Nerbini, attempted to imitate the graphic style of the artist Alex Raymond.”

It’s a tantalizing prospect that Fellini’s fledgling career in writing began in comics, especially as he would be Dino De Laurentiis’s first choice to direct the 1980 movie version of Flash Gordon, but fumetti expert Leonardo Gori suspects that Fellini’s foray into writing Flash Gordon is sadly the stuff of legend. “Nerbini never produced a [Flash] Gordon ‘follow-up’, at least before the war. [Gordon] returned to Italy only in 1944-45… and only in books based mainly on the originals.” Any additional artwork for these, Gori explains, was drawn not by Toppi, who died in 1942, but by the more modest craftsman Guido Fantoni. As for the texts for these sections, Gori asks, “... Were those made ten years earlier by Fellini? Our opinion is no, their artistic level does not seem compatible with the volcanic imagination of the author of Roma and Juliet of the Spirits.” But who knows, perhaps they will surface one day miraculously from some private archive, like in a Fellini film? In the meantime, only two actual comic series by Fellini have been unearthed, Giacomino, and Cico e Pallina published in the Thirties humour magazine Marc’Aurelio.

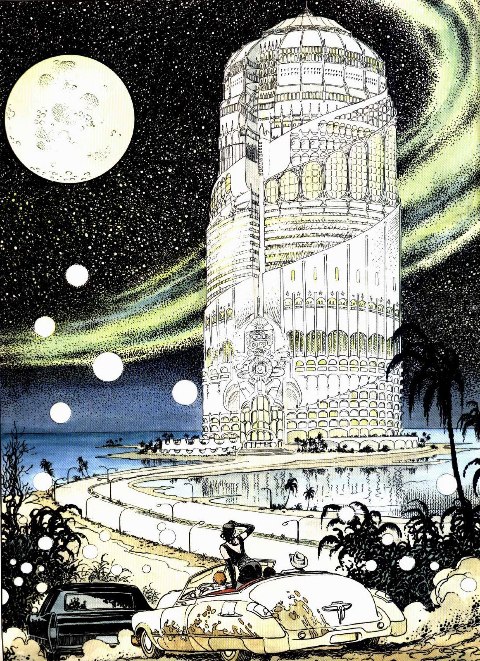

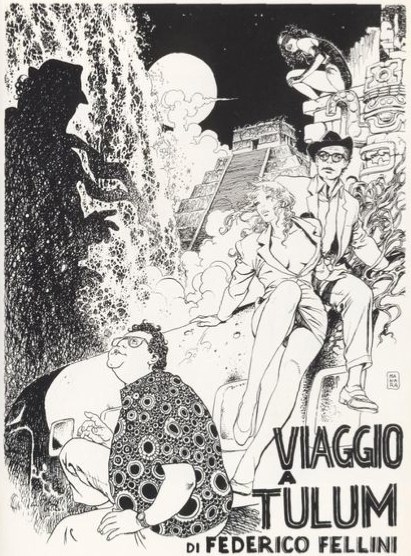

What is certain is that Fellini’s love of comics often spilled over into his movie-making, for example in The White Sheik’s satire of soap opera photo comics or Mastroianni’s cameo as Mandrake in Intervista. Similarly, in 1990, Fellini told Vincenzo Mollica, “I constructed and recounted [Amarcord] after the sobre frames of the legendary American comic strips of the Thirties.” The meeting between Manara and Fellini, twenty-five years his senior, proved that their admiration was mutual, each recognizing in the other their alluring and singular way of reflecting and representing the real and imagined world, but it did not result immediately in a collaborative comic. Instead, Fellini invited Manara to provide illustrations to accompany his prose story Trip to Tulum, serialized in May 1986 in six parts by the evening newspaper Corriere della Sera in Milan. This was trumpeted with the announcement, “For the first time, the great director reveals the plot of his next film”.

The truth was more complex. Viaggio a Tulum, to give its Italian title, had begun as a project inspired by Fellini’s troubled fascination with the books of Carlos Castaneda, in particular The Teachings of Don Juan, and by the almost mythical beauty of Tulum’s sea, a location suggested by his Mexican assistant for his 1980 movie City of Women but not used. After discussing the project with Castaneda in Rome in October 1984, Fellini joined him on a trip to the Yucatan in Mexico to explore making a film together about the mystical Peruvian writer’s initiation journey in Mexico while researching his student thesis about psychotropic plants. The project collapsed, however, after the author vanished, amid stories by Fellini about a cabal of cultists who were devoted to the book and to protecting its secrets.

And it might have all ended there, after Fellini’s own shamanic adventure concluded in the press, had Manara not gone back to him, eager to collaborate and transform it into a graphic novel. Reluctant at first, the director later commented, “I was already familiar enough with Manara’s talent to know that the drawings would be beautiful.” What also persuaded him was “..the notion that seeing the story transformed into a graphic novel would vanquish once and for all any minute remainder of my impetus to make it a film.” Manara made a start but Fellini had different ideas, preferring to open earlier in the tale at the Cinecittà film studios and persuading Manara not to use Fellini’s likeness as the leading role, but to re-cast ‘Snaporaz’ and have him played by Mastroianni.

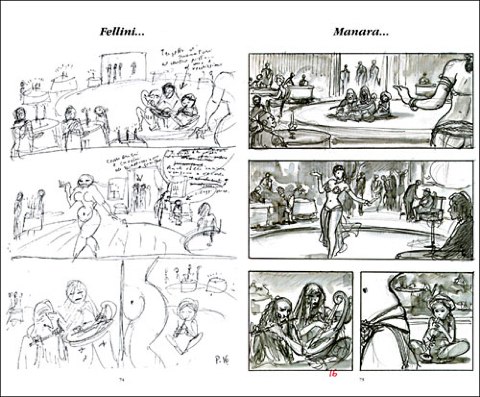

The whole collaborative process was intensive and intimate, as Manara later recollected. “With Fellini I worked in a very direct way, we met often and he gave me lots of detailed storyboards for each page (he really enjoyed drawing), with shots, dialogue, etc. Throughout he remained the director and I was only his cameraman. Fellini gently infused his spirit, breathing it in from images to dialogue, from dialogue to action.” First published as a graphic novel in Italy in 1989, the result blossoms into a beautiful, lyrical, literal ‘trip’ into two exceptional imaginations in harmony, each inspiring the other, interweaving from panel to panel.

Somehow, the aura of this unfilmed, perhaps unfilmable, film continues to resonate in unexpected ways to this day. In 2011, Palermo journalist Laura Maggiore wrote a thorough 216-page study entitled Fellini e Manara for Navarra Editore in Sicily, while at the 2011 Moscow Film Festival, Fellini’s former Mexican-born assistant Tiahoga Ruge premiered his film Soñando con Tulum [‘Dreaming about Tulum’]. This is a fictionalised version of Fellini and Castaneda’s strange exploits crossing Mexico, although Castaneda could not appear by name due to his heirs’ strict control of the rights to his work. Ruge has told E J Albright on the American Egypt blog (June 30th 2011) that he intends his film to be the first of a pair, the second potentially adapting the graphic novel itself for the big screen. A ten-minute teaser for this project can be seen below.

Journey To Tulum - teaser from Franco Valenziano on Vimeo.

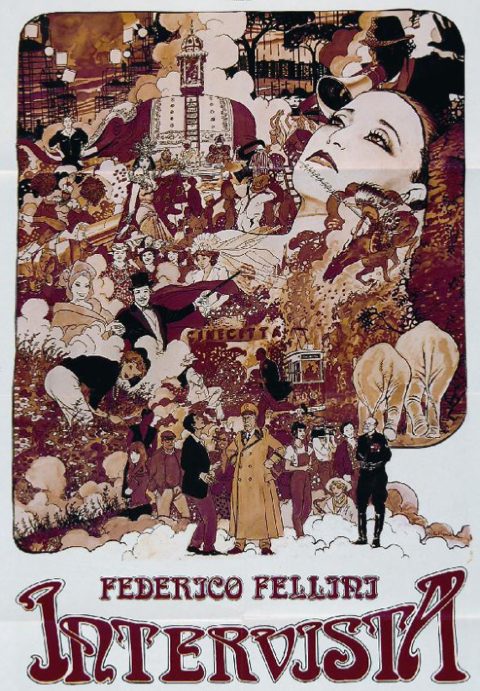

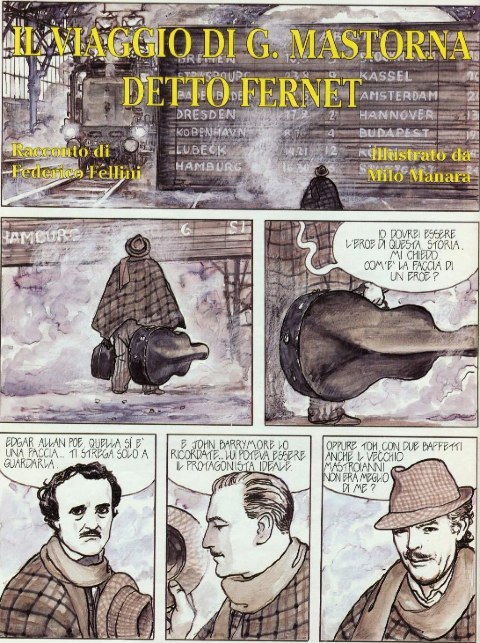

The joint journey of Manara and Fellini was too special and fruitful to end with their Trip to Tulum. Manara illustrated the film posters for Fellini’s films Intervista in 1987 (above) and La Voce della Luna in 1990 and the two men would reconvene in 1992 for another ‘trip’ together into that mysterious realm between cinema and comics. Il viaggio di G. Mastorna (‘The Voyage of G. Mastorna’), was another proposed film which Fellini had described as “the story of a dead man who does not know it yet”. He came to see this project as his life’s curse, after his failed attempts through most of his career to bring it to the screen. Even after he had built sets and shot film tests, Fellini abandoned the project at the last moment. Legend has it that a magician had once warned Fellini that if he ever made the movie, it would be the last he ever made.

Instead, Fellini eventually agreed to reunite with Manara to convert his screenplay into a graphic novel for the deluxe Italian comics magazine Il Griffo. Manara became a vehicle through which Fellini could rid himself of the negativity dogging this project and perhaps to face his own mortality. They portray the travels of their unknowingly dead leading man, a cellist clown, wandering in the afterlife, whose atmosphere is evocatively tinted in watercolor washes of sepia and blue. Unfortunately, when the first of a planned three episodes was printed, the publisher mistakenly added the word ‘End’ to the last page. Fellini never wanted to put ‘The End’ at the conclusion of his movies, and seeing this as an ill omen, the superstitious Fellini, aged 72 and in poor health, decided to stop his adaptation right there. Six months after publication, Fellini passed away. Those second and third parts would never see the light of day. Tantalizingly, one the world’s most famous unfilmed movies was also left uncompleted as a graphic novel.

Over the years, this intriguing collaboration has also taken on a life of its own. Recently, Manara was interviewed about it by Canadian film-maker and Fellini fan Chelsea McMullan for her short documentary for Fabrica called Derailments, premiered at the 2011 Toronto Film Festival (see trailer below). When McMullan visited Manara’s studio in Verona, she watched as, “Out of a wooden drawer, Manara started to pull out a thick pile of cloth napkins. On each napkin was a sketch, some quite elaborate, others just faded lines and shapes. Manara explained that he and Fellini would often go out for dinner to discuss the project and inevitably every time Fellini would start sketching out his ideas on a napkin. He pulled out napkin after napkin soiled with Bolognese, wine and olive oil. He looked deeply nostalgic as he neatly folded and tucked away the remnants of many shared ideas and meals.” This cabinet of memories holds the only remainders of their second creative voyage together.

DERAILMENTS from Fabrica on Vimeo.

In more recent years, Manara has revisited Fellini’s career, for example by interpreting unforgettable scenes from his greatest movies in a series of signed, limited edition prints (above). Many of Manara’s other tales compiled in the third Dark Horse volume are unmistakably suffused with the director’s vibrant celluloid surrealism, his soaring flights of fantasy, his love for women, his love for life. Theirs was a rare meeting of two marvelous minds and imaginations, a close encounter left unfinished, but never ending, continuing today as their stories reach a fresh audience thanks to this new edition. Manara and Fellini invite us to explore their wonders and dream along with them. Endlessly.

Posted: September 14, 2012

This Article originally appeared as the Introduction to the third volume of the Milo Manara Library, published by Dark Horse Comics in 2012.