Diabolik & Fumetti Neri:

The Italian Comics Connection

As my final Article of 2012, let’s celebrate this year’s Golden Anniversary of an iconic comic character, who if he had been less adult and complex, and all-American, would probably be a global media phenomenon by now as big as Spider-Man. Looking back fifty years, one revolution in comic books was already gaining momentum in New York City at the Marvel Comics offices with the debut of Stan Lee and Steve Ditko’s Spider-Man, the first solo teenage superhero with believable hang-ups and self-doubts. By humanising their pantheon and connecting them within one shared universe, the Marvel Age of Comics would redefine the genre. But elsewhere in that same year, 1962, another daring and disturbing revolution in costumed characters was being triggered in Milan, Italy, by a small publishing house called Astorina, run by sisters Angela and Luciana Giussani (photos below of Angela from 1946 and of Luciana from 1948 when she won the national ‘Miss Sport’ prize).

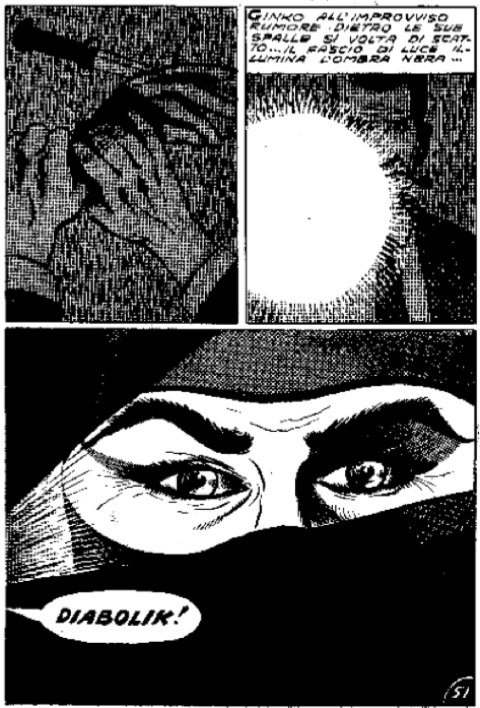

Forget Superman’s ‘Truth, Justice and the American Way’, or Batman’s revenge complex, or the soap-opera anguish and responsibility of a Marvel superhero; the enterprising Giussani sisters sensed that the time was ripe for a very different, more disturbing kind of male lead in Italian comics. Their star would be sinister yet seductive master thief who is more of an amoral villain than an altruistic boyscout or vengeful vigilante. He had no civilian secret identity and no qualms about stealing from his fellow felons, and if necessary killing them, often with his deadly blade. He was a women’s fantasy figure, his rippling physique encased head-to-toe in a skin-tight, jet-black bodysuit except for a gap in his cowl to reveal his thick eyebrows and piercing eyes. To fit his dark appearance and even darker soul, the sisters came up with the devilish name of… Diabolik.

The Giussanis took inspiration from their favourite Hollywood actor Robert Taylor and artist Enzo Facciolo based a gesso bust on him to use as a model for the character (below). In some ways, Diabolik’s pronounced, brooding features came to resemble more closely those of Sean Connery, whose debut as James Bond in Dr. No was released in 1962. In November of that year, the first criminal-turned-anti-hero in Italian comics hit the newsstands in ‘The King of Terror’, drawn by Angelo Zarcone (below) with a cover by Brenno Fiumali.

In November 2012, for his 50th anniversary, Sky TV in Italy announced a new TV series (see promo photo at the start). Originally, In 1963, in the introduction to the first reprint of his stories, Diabolik was described as “...a man of extraordinary intelligence and boundless audacity. His powers seem supernatural, in fact Diabolik is the man of a thousand disguises. With his special mask of plastic of his own invention, he can transform the features of his face; with tinted contact lenses he can change the colour of his eyes; and with other infinite tricks he can modify his athletic physique into a body that is old, sagging, fat or ruddy. With these remarkable transformations he can camouflage himself as he pleases and evade his adversaries no matter how difficult or desperate the situation. Only one man will absolutely not surrender to Diabolik: Inspector Ginko, head of the Homicide Squad, who has hunted this phantom criminal worldwide for years. In this almost inhuman struggle terrible events conspire together through the evil cunning of Diabolik and the sharp genius of Ginko.”

Long before Diabolik, super-criminals had starred in popular prose fiction going back at least to French characters like gentleman burglar Arsène Lupin by Maurice Leblanc in 1905, hooded Romany gangster Zigomar by Léon Sazie in 1910, and Parisian ‘genius of evil’ Fantômas by Marcel Allain and Pierre Souvestre in 1911. Before them there was also the British ‘amateur cracksman’ and master of disguise Raffles, created in 1898 by E.W. Horning, brother-in-law of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Most of these rogues had later appeared in comic-strip versions, Fantômas enjoying a long run in Mexico. While drawing on these fiendish forerunners, Diabolik stands as a thoroughly modern comics creation of the Swinging Sixties, driving the latest black Jaguar E-Type launched in 1961 and teaming up from his third issue (below) with a very capable blonde partner, in crime and in bed, Eva Kant, modelled on Grace Kelly.

As for his origins, these would not begin to be disclosed until the cult story in the fifth of the fortnightly issues published in 1968. Imprisoned with his nemesis Ginko, Diabolik finally replies to the inspector’s questions by exclaiming, ‘I don’t know who I am!’ It is revealed that a crimelord named King took him under his wing as a shipwrecked orphan and trained him to be the successor to his hidden island empire. It was here that a Dr. Wolf taught him to make his famous masks. The protegé rebels by murdering and robbing King and taking on his appearance to quit the island and destroy his organisation. Nameless, he calls himself after a pet black panther to which his mentor had compared him, by the name of Diabolik. Gradually, over the years, more of the cast’s buried secrets would be revealed.

From a moneyed middle-class family, Angela and Luciana Giussani (above) were part of the Milanese jet-set. As shrewd businesswomen, they founded their publishing company Astorina in 1961. They spotted a lucrative gap in Italy’s booming newsstand market for novels in comics form, small enough to hide in your pocket, long enough to last your train journey to or from work. They based their new product on the traditional compact paperback format of a ‘giallo’ or yellow, the Italian term for a crime story, using its luridly illustrated card covers and 128 black-and-white pages inside, putting two panels per page. With the logo in ragged red brushstrokes as if scrawled in blood, Diabolik was initially billed as ‘the comic for thrills’ (see poster for the second issue below), then from late 1965 as the ‘giallo in comics’, offering a ‘complete novel for adults’ for only 150 lire. Perhaps wisely, the sisters signed their stories as ‘A. and L. Giussani’ out of fear that the public would not buy such a comic written by two women. Diabolik rapidly became a hit, shifting from quarterly to monthly with its third issue, then coming out every two weeks from January 1965, demanding yet more scripting and illustration collaborators.

Why did Diabolik prove so popular at this time? Partly, it suited the mood of the times. Since the late Fifties, Italians had been rocked by rapid financial, industrial and social changes. An economic miracle was encouraging thousands to abandon agriculture and work in factories and offices. Mass migration to Northern cities like Milan resulted in a rise in literacy, disposable income, and cut-price reading matter. To cater to this expanding readership, Italy developed a massive and diversified periodical market, distributed, until 1999, solely by a powerful union via a phenomenal 37,000 newsstands.

Diabolik also tapped into many people’s deepest, most selfish fantasies. As Astorina’s current director, Mario Gomboli, explained in That’s Fumetti in 1998, “... [Diabolik] did not think twice before taking what he wanted, nor before doing what he had set his mind on doing. This was the very incarnation of the unconfessed aspirations of much of the human race.” The series also reflected growing unease about consumer society, capitalist greed and political corruption, by asking, “Who are the real villains?” Gomboli states that Diabolik’s readers “...realised that most of the victims of his ruthless dagger, even though they wore a suit and tie and not Diabolik’s black, hooded sweatsuit, were even greater villains than he was: corrupt politicians, drug-pushers, usurers, tycoons, who would stop at nothing to amass ever greater wealth.”

Diabolik pushed against decades of stifling censorship and the moralistic repression of the Catholic church and helped to pave the way for greater liberalism in the Sixties. In 1962, Italian publishers of children’s comics had introduced the ‘Garanzia Morale’ or moral guarantee (above) as a seal of approval similar to America’s Comics Code Authority to impose a certain political correctness and allay teachers’ and parents’ anxieties. To sidestep this, Diabolik declared that it was ‘for adults’ on its covers and it was soon followed by a flood of other ‘fumetti neri’ or black comics, which copied its format, formula and arresting one-word name, often using that criminalising letter ‘K’, and spicing up the crime with sexual and horror elements.

The earliest of these copies in June 1964 was Fantax (above), working as detective John Marquall within the law, but hunting down criminals in his skeleton costume. To avoid confusion with the original French Fantax created in 1946, the series changed names to Fantasm in 1965 and ended with its 23rd issue in August 1967.

Two superior fumetti neri were Kriminal (above) and Satanik, created in August and December 1964 by Max Bunker and Magnus, pen-names of Luciano Secchi and Roberto Raviola, for Milan publisher Andrea Corno. Kriminal had grown up as Anthony Logan in a reformatory and after taking revenge against the man who drove his father to commit suicide, he warps into a sadistic killer, dressing in a full-body, black-and-yellow skeleton costume. Satanik (below) started life as the disfigured Marny Bannister, shunned even by her own family, who wreaks vengeance when she transforms herself into a beautiful, heartless killer and an unstoppable symbol of women’s sexual power. Commercial hits, both titles lasted until 1974, Satanik drowning in her 231st issue, Kriminal appearing weekly for most of his 419 issues.

Another successful spin-off from Diabolik, published by Angela Giussani’s husband, Gino Sansoni, was Zakimort (below - 1965-72, 91 issues). Black-haired Fedra Gallant is the rich and charming young heiress of her assassinated criminal father. Living a double life, she dons a black leotard and blonde wig to eradicate his killers and all criminals without mercy, assisted by strongman Leo and marksman Teddy. Little does Fedra’s boyfriend, police lieutenant Norton, realise that his elusive enemy Zakimort is the woman he loves.

The fumetti neri explosion threw up a horde of other bizarre protagonists. Mister X (53 issues, 1964-8) was a super-fiend inspired by Fantômas, while Sadik (below - 62 issues, 1965-7) was as ruthless as The Punisher in his black suit which became impenetrable thanks to a regenerative bath.

Weirdly misspelled with a ‘J’, perhaps to mimic Diabolik’s ‘K’, Jnfernal (28 issues, 1965-7) was the world’s ‘public enemy number one’, whose mask enables him to change his face. Malevolent mastermind Genius began in 1966 as a photographic comic, switching in October 1968 to comic art, some of it by a young Milo Manara.

Spettrus (above - 50 issues, 1965-7) was the immortal ghost of scientist Marcus Emerson, whose glowing eyeballs possess other people’s bodies and feed on fear. In his first incarnation, Demoniak (below - 30 issues, 1965-7) was another scientist, this time intent on inventing a super-race to rule the world; his brief second version in 1972 was practically a clone of Diabolik. Cobrak, Killing, Masokis, Tenebrax, Terrore and Venus were just a few more of this boom-and-bust craze, some never going beyond one issue.

At their best, these provocative Italian comics were delivering more complex, even perverse anti-heroes and anti-heroines than anything anywhere else in global comics in the Sixties, but not everyone was pleased, especially once the format was adopted for other increasingly explicit erotic comics. Since its third issue, Diabolik had been the target of a long series of official complaints and criminal charges, of which publishers Astorina were entirely acquitted. A press campaign across the political spectrum, from the Catholic right to the Communist left, soon spread a moral panic to suppress these provocative little publications.

One scare-mongering cover story in La Domenica del Corriere of April 4th 1965 (above) told how “...Milanese employee Bruno Parini, tired of not finding dinner ready because his wife spent her time reading these comics, borrowed from a friend a carnival costume like Diabolik’s and dressed like this, burst in at night on his wife. However, the sudden shock to his wife Franca was greater than expected and she had to recover in a private clinic for nervous conditions. Now luckily the lady has recovered; she will not be reading any more of these comics.” A month later, a magazine claimed that a Sicilian wife had poisoned her husband, allegedly inspired by the piles of fumetti neri she avidly consumed, especially Diabolik.

More seriously, the front page image of the weekly Tribuna illustrata of October 2nd 1966 (above) showed Fantax, Satanik, Sadik, Demoniak and Kriminal (but not Diabolik) behind bars. The accompanying debate in its pages came ahead of a court case in Milan against the publishers, directors, printers and distributors (but not the creators) of Kriminal, Sadik and Satanik on the charges of glamorising crime and disrupting all sense of shame. In February 1967 they lost the trial and were heavily fined. As a concession, publisher Andrea Corno asked Max Bunker to soften his storylines. In the special colour 100th edition of Satanik (November 6th, 1968), Bunker refers to the changes he made to his heroine after two such convictions and the company’s internal self-censorship, concluding “Satanik is not perverse. She has given free rein to all her repressions to acquire a certain equilibrium which has led her to become more mature and more human.” Fumetti neri would no longer be as black as they had once been.

Different times needed different heroes or anti-heroes. Comics historian Matteo Stefanelli believes that “Fumetti neri were a sort of ‘dark side’ of the Sixties Italian ‘miracle’: the country was improving, but Diabolik revealed what was ‘hidden’ behind the boom: abuses, economic differences, egoism, violence. But I see no anti-authoritarian attitudes in them. Later, in the era of punk, writer Stefano Tamburini’s roots were in the youth movement of 1977, libertarian, creative, more linked with radical and extreme leftist stances.” In the spring of that year, after the defeat of the student occupation of the University of Bologna, many young Italians felt left out in the cold. In 1978 Tamburini founded his own underground magazine, Cannibale, in which he created the story of a student who “projects his repressed rage into the mechanical hoodlum he has built himself with parts of a photocopy machine stolen from a university building.” Tamburini wrote and drew his irrational, absurdly violent robot Rank Xerox himself (above), with help from other cartoonists and, appropriately, a photocopy machine.

In 1980, the illustrator Tanino Liberatore (above) brought a stunning hyperrealism to Tamburini’s Rank Xerox and the chaotic circus of his near-future Rome, when Tamburini brought the series to the colour pages of the new cool magazine, Frigidaire. Out-of-control, the overmuscled, pig-nosed mechanical brute became the sextoy of Lubna, a precocious Lolita, and in one notorious scene, crushed the hand of an irritating girl pestering him to buy her flowers. It wasn’t long before the Rank Xerox corporation objected to the association of their product with a character “whose adventures are a concentration of violence, obscenity and foul language”, so Tamburini and Liberatore eventually conceded and renamed him Ranxerox. It became an international sensation, translated with some censorship in Heavy Metal magazine in the USA. Tragically, further adventures and a projected movie adaptation came to a halt in 1986 with Tamburini’s early death.

The same year brought an extraordinary new character to the pages of Frigidaire’s offshoot Tempi Supplementari. Ramarro (or Lizard - above) is the first masochistic superhero, whose only goal is to make himself as evil as possible in the most bizarre ways. Like his reptilian namesake, whatever you break off him will grow back. Creator Giuseppe Palumbo explains that Ramarro is “the punk son of a ‘normal’ family of self-righteous superheroes, who rebels against them and decides that the only ‘sensible’ decision when he discovers his superpowers is to use them against himself.”

Palumbo acknowledges his green-skinned outsider owes a lot to the anarchic DNA which Magnus’s comics transmitted to him as well as all of the Frigidaire gang. Ramarro is also Palumbo’s response to seismic changes during the late Eighties and early Nineties, such as the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Chernobyl disaster, and the exposure of widespread bribery in the Italian government, “which gave me the sense of a world where the only way of life was madness and masochism.” In 1991, Ramarro was reinvented with writer Daniele Brolli for Cyborg, Italy’s first cyberpunk comic magazine, and his universe has continued expanding in subsequent series.

Through all these changes and competitors, Diabolik, the original, has survived, written and published by the Giussani sisters throughout their lives (Angela dying in 1987, Luciana in 2001). It is still huge in Italy, with an exhibition coming home to Milan last November and numerous celebrity fans, such as fashion designers Dolce & Gabbana, for whom “Diabolik is a legend. We’ve been reading it since we were young. He is a male icon: he’s got a perfect body, a beautiful woman and lives in amazing hideouts. Yet he is also a robber and a thief with a penchant for diamonds. Deep down, we are all criminals like him…” Fittingly, over the past decade, Palumbo has been among the series’ outstanding new illustrators (above). “To me, Diabolik is totally devoid of humour or irony, whereas I think irony is essential to my stories and my outlook on life. So drawing Diabolik, I am trying to channel all the dark and serious side of me.”

While Mario Bava’s 1968 movie adaptation of Diabolik is admired as a Pop Art classic, Italy’s greatest masked anti-hero had to wait until 1986 for two of his comics to appear in English and only six more in 1999 have appeared since. The animated TV version in 2000 proved too morally questionable for American viewers and had to be censored, whereas the 2009 video game sold well enough. Can Diabolik cross over? Palumbo reflects, “For years there’s been talk of a live-action movie. If Tarantino or Besson were keen, they’d be perfect. I’d like Guy Ritchie. But I fear all three would be tempted to add a pinch of irony, which, as I said, would be lethal!” Meanwhile, below is the trailer for the first in a live-action Italian TV series on Sky Movies HD. What better way to start another Diabolik-al fifty years!

Posted: December 30, 2012

This Article originally appeared in Comic Heroes Magazine 14, Sept-Oct 2012.