Crime Does Not Pay:

America’s First & Greatest Crime Comic

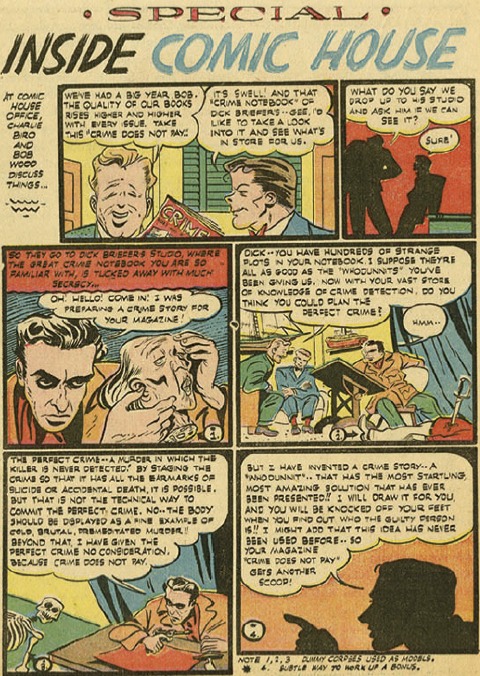

Crime most definitely did pay in 1945 for publisher Lev Gleason, and presumably also for editors Charles Biro and Bob Wood, as the four issues, #38-41, reprinted in Volume 5 of the Crime Does Not Pay Archive series from Dark Horse Comics, testify. It’s not common practice to give cover billing under the logo to a comic book’s editors. In fact, Biro and Wood also make rare cameo appearances inside Crime Does Not Pay #38 in a ‘Special Inside Comic House’ page to introduce Dick Briefer’s regular Crime Notebook feature, Who Dunnit?, in which readers are challenged to solve a murder mystery. Briefer shows his two editors at ‘Comic House’ in celebratory mood: “We’ve had a big year, Bob. The quality of our books rises higher and higher with every issue.” Biro might have added, “And our sales too”.

The pair go to visit the studio of Briefer, thirty at the time, who draws an amusingly sinister self-caricature with a murderous, sunken stare. He brings to this story much of the macabre humor that he was also applying at the time to his humorous makeover of his Frankenstein series over at Prize Comics. His footnotes explain that the studio is cluttered with “dummy corpses used as models” and that his hyperbolic claim for this issue’s Whodunnit is a “subtle way to work up a bonus.” Briefer’s playfulness continues with some surprising missing panels, first on page four where he leaves the space blank and addresses the reader directly saying, “Let’s rest here a second. What a bunch of bums!!” He then leaves still more empty spaces on pages six and seven- it’s one way to cut corners and make production time briefer!

Briefer wrote his own material, while Dick Wood is credited for scripting most of the main opening yarns, each allegedly “A True Story adapted for Crime Does Not Pay” and delivers some of the obligatory text stories. As for the artistry in Crime Does Not Pay during this period, overall it is a curious mixture of milder cartoonish looseness, best exemplified by Briefer, less well by other artists like Art Mann, or Al Fagaly on his unconventional ‘Meek Murderer’, alongside attempts at a more noirish shadowy moodiness, from the vampish dames and demons of Rudy Palais to Jack Alderman’s slightly stiff but more detailed renderings (below). The amount of black ink on the page is one indicator of the darkness of a story’s tone here. Working on some lead stories is ‘Bob Q. Siege’, a pen-name for Robert Q. Sale, who was a journeyman artist at best. His whole page panel in #39 is unusual but its composition lacks impact. Other amateurish uncredited artists, for example on the opening story in #40, employ some awkward layouts and have to resort to arrows to direct readers from one panel to the next.

The top-hatted pied piper Mr. Crime is joined by a new spectral host, Officer Common Sense, formerly John O’Shay, whose ‘secret origin’ is told in a longer fifteen-page opener to #41. Both sides of the tussle between good and evil could now be personified in the competition between the devilish Mr. Crime and the angelic Officer Common Sense (below), although the sanctimonious ghostly cop would not have the appeal or staying power of his diabolical opposite.

It is well known that you can’t always judge a comic book by its cover. Charles Biro’s eye-catching illustrations on these four issues’ covers pack real punch which the interiors don’t always live up to. Biro is notorious for the wordiness of his scripting, so it may come as a surprise to see how adept he is at the wordless images he draws here. They promise grimmer and grittier dramas within, like #39’s sinister scene (below) of crooks dumping into the river a locked trunk with blood dripping out of its lid, but nothing like it appears inside. That policy would shift in a year or so’s time, when most of Biro’s covers would directly relate to stories which he began to write himself inside.

In Bill Spicer’s magazine Fanfare #4 (Summer 1981), Art Scott attributes “a sudden quantum leap in quality with issue #49 of Crime Does Not Pay” to Charles Biro, who set about “...cleaning house in the crime department”. Though uncredited, Biro’s handiwork is self-evident from this point in the much longer and denser opening tales. Scott comments, “Suddenly the lead stories were twice as long, three times as complex, and had four times the lettering.” As a writer, Biro typically packed nine panels into a page and filled them up with plenty of dialogue and thought balloons, seldom using captions for narration. His covers also became less poster-like and more filled with speech balloons and promotional texts. It’s a sign of Biro’s success that Crime Does Not Pay switched to monthly frequency with #51 in May 1947.

But all that was still two years away from this quirky quartet. Change is in the air, though, as Briefer leaves his gig with #41 and a tougher, more atmospheric and realistic approach would gradually darken the tone of America’s first and greatest crime comic. Biro and Wood would have many more “big years” to come and the quality would rise still “higher and higher”.

(As a footnote, two later Crime Does Not Pay classics by Bill Everett and Klaus Nordling are reprinted in The Mammoth Book of Best Crime Comics which I edited in 2008).

Posted: May 12, 2013This Article originally appeared as the foreword to Crime Does Not Pay Archive Volume 5, published by Dark Horse Comics.