Orijit Sen:

His River of Stories

The son of a cartographer for the government, Indian cartoonist Orijit Sen (born 1963) and his family would be posted to a new location every few years. “Perhaps that developed in me an empathy for ‘outsiders’ and people who didn’t fit in,” Sen reflects. Comics have been likened to maps, of time as well as space, their grids and iconic graphics enabling readers to navigate a narrative. Whereas his father recorded his environments into official topographies, Sen would go on to chart the places and people around him into personal and often political stories.

While devouring whatever home-produced or imported comics and political cartoons he could get his hands on, Sen also admired Satyajit Ray’s films, and “wanted to make comics that would offer the same kind of immersive atmosphere and detail”. The uncompromising American underground comix of Robert Crumb and Art Spiegelman were a revelation when Sen discovered them during his graphic design studies,. “I learned a lot from reading their stories, observing their styles and even copying them.”

In 1990 Sen and his wife started a studio and store called People Tree in New Delhi to bring together designers, artists and craftspeople in diverse media from textiles to terracotta on a genuinely equitable and collaborative platform - in opposition to the then prevalent model, in which the designer (head worker) tells the artisan (hand worker) what to make. In 1994 Sen won a grant from Kalpavriksha, a Delhi-based environmental organisation, to create and publish his first full-length comic, documenting the building of the contentious Sardar Sarovar Dam across the Narmada River in Western India. He visited the valley for several weeks, researching, sketching and talking with residents who were being displaced by the development and with activists protesting alongside them.

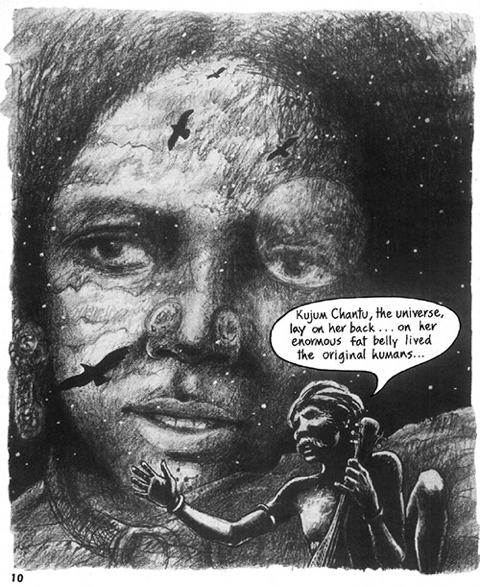

Combining these stories with lyrical indigenous myths and sensitive grey-toned drawings, the result is the passionately biased River of Stories, originally published in English and translated into Hindi in small photocopied batches, but to be republished as a revised edition next year. “I still meet people who tell me they read River of Stories years ago and it helped change the way they look at development, ecology and the rights of indigenous people in India,” says the artist. It is recognised by today’s Indian graphic novelists as the country’s first non-fiction graphic novel.

Sen digs into Indian history in his new Strip for ArtReview Asia (below) about a heroic but little-known Dalit (untouchable) woman called Nangeli from Kerala in the early nineteenth century. This is the latest in Sen’s catalogue of shortform, often documentary comics, from his early slice-of-life series ‘Telling Tales’ in India Magazine (1995–7) to ‘The Girl Not from Madras’, with journalist and writer Neha Dixit, a true story about human trafficking published in First Hand: Graphic Nonfiction from India, an anthology Sen coedited earlier this year. Two new graphic novels are in gestation, while Sen also works ‘off the page’ on art projects. Since 2013 he has been collaborating with students from Goa University, where he is a visiting professor, to investigate one of Goa’s oldest marketplaces, in the ‘Mapping Mapusa Market’ project. Like father, like son: in all his work Sen keeps a keen sense of place.

‘A Travancore Tale’ by Orijit Sen for ArtReview Asia magazine

Click images to enlarge…

Web-Exclusive Interview with Orijit Sen

Orijit Sen generously responded to my enquiries by email for the above piece. Here below is the full text of our email interview:

Paul Gravett:

Do you see yourself as ‘India’s first graphic novelist’ as others have described you? I wondered what you made of G. Aravindan’s comic strip Cheriya Manushyram Valiya Lokavum? Were their other pioneers in the press that paved the way for you?

Orijit Sen:

Personally I don’t place much significance to being called ‘the first’. Yes, I was one of pioneers of the form in India, and what that meant for me was above all a strange sense of isolation - one that comes with being immersed in something that nobody else gets! When I came out with River of Stories, there were no publishers, readers or reviewers. My desire to tell stories through comics was of course influenced by a host of Indian, European and American comics that I grew up with. I was also looking at political cartoons and satirical pieces by great Indian cartoonists like R.K.Lakshman and Abu Abraham. I wonder now why none of them attempted longer form stories. Unfortunately, I did not end up seeing G Aravindan’s wonderful work till after I did River of Stories. Needless to say, I loved it when I did. I wished I had come across it earlier - I wouldn’t have felt so isolated!

Who were your antecedents and inspirations who were creating comics in India - did you meet and learn from any of these forebears of yours?

While in school. I used to devour Phantom, Tintin, Amar Chitra Katha, Bahadur, Nonte Phonte and whatever else I could get my hands on. I admired Satyajit Ray’s films and stories a lot, and wanted to make comics that would offer the same kind of immersive atmosphere and detail. Later, in college, I came across Art Spiegelman and Robert Crumb. I learnt a lot from reading their stories, observing their styles and even copying them. I never had any interactions with comics makers till much later in my adult years.

I am curious about your family background and upbringing and what were the decisive influences on your personal principles and politics and on applying them to making art?

My father was a cartographer working for the Indian government, and my mother was a home-maker. My father would be posted to a new location every few years, and we moved with him. As a result my brothers and I grew up in various different parts of India. Perhaps that developed in me an empathy for ‘outsiders’ and people who didn’t fit in. I was myself quite rebellious in my teen years, and often took pride and pleasure in provoking teachers, prefects, bullies and other authority figures. My family was middle class, not very religious and generally progressive, but not political at all. I was close to my brothers, and my elder brother Abhijit introduced me to a lot of ideas by way of the art, music and books he himself was interested in.

I find it frustrating here in the UK that we don’t have many more Asian-British creators of comics. It seems parental pressure to qualify for a secure profession and genuine concerns about the difficulties of making a living as an artist, can result in many young hopefuls not pursuing their hopes of becoming an artist. Was this your experience? Is this attitude changing at all now?

Yes, we were all brought up to become doctors, engineers or bankers, and things aren’t too different for Indian kids even now. My brothers and I each had to rebel in our own ways in order to become a journalist, a writer and an artist respectively. I have no idea what gave us the confidence to reject the prescribed path back in the 70s, when career opportunities were much more limited than they are now. Just the impetuousness of youth, I suppose! I was the most rebellious and headstrong, and I’m afraid I gave my poor parents a lot of cause for worry!

Tell me about your meeting with one of your big heroes and influences, Robert Crumb, a guest with his wife Aline at the 2nd Delhi Comic-Con.

Just before the Comic Con, someone had asked me if I wasn’t excited at the prospect of meeting R.Crumb, and I had replied ‘Yes, but I guess I would have been more excited ten years ago.’ But the Crumbs proved to be even more inspirational up close, in the flesh, than as distant divinities—for they possess a quality that has nothing to do with media hype. It’s a quality that comes from elsewhere—from their immense personal and political honesty, from their lifelong commitment to their craft, and from the depth of their partnership as artists, lovers and grandparents. Robert and Aline cancelled a prior plan to visit Jaipur the following day, and came over instead to my studio for lunch and a gathering with friends. I felt privileged to be able to show them some of my work. Robert didn’t say too much, but the way he looked at my drawings was very gratifying. He didn’t just look. He LOOKED – his eyes behind those owlish glasses roving over the pages, drinking in every detail, not missing a thing. We exchanged a few technical notes about perspective and tones and that sort of thing, and even some about balancing the demands of work and family! Finally, he said with just a little mischief in his eyes, “I love the way you draw trees. I think I’m going to steal your way of drawing trees!” Steal my way of drawing trees… indeed. Nothing would please me more!

How did your cartooning and comics-making get underway, what were your training, first projects and publications (self-published or commissioned)?

I started drawing my first comic when I was about 12 or 13. The immediate provocation was Tintin, if I remember correctly. I was fascinated by the way I could ‘enter’ the world of those stories and travel to distant lands with Tintin, Captain Haddock and the others. My first project didn’t get past page 1. But soon I started on another one. I couldn’t go too far with that either, and abandoned it. But a few weeks later, I launched a third project - and so on it went. I must have conceived at least a dozen projects through my high school years. I never managed to complete a single one, but I believe I learnt a lot about visual storytelling in the process. I did a couple of shorter comics pieces while in college, but in fact River of Stories was my first completed full-length comics project.

Please tell me why People Tree was founded in 1990 and how it operates today.

I married Gurpreet Sidhu, my girlfriend from college, in 1989, and we started People Tree together in 1990. Our idea was to create a studio-cum-retail store that could bring together designers, artists and craftspeople on a genuinely collaborative platform - in opposition to the prevalent model at the time, in which the designer (head worker) tells the artisan (hand worker) what to make. We sought to create contemporary handcrafted styles and wanted to reach out to our customers directly, rather than produce work for clients. We experimented a lot with textile printing, because, as you know, India has such wonderful and rich traditions of textile design. Last year, V&A featured a T-shirt we designed and produced back in 1998 for its The Fabric of India exhibition, and it felt good to be acknowledged as having contributed a small but new fragment to the amazing history of Indian textiles. People Tree has of course grown much since its inception, but we’ve stayed with our original vision, and resisted offers and attempts to turn its brand value into a chain store enterprise!

I wondered if Joe Sacco’s cartoon journalism, and the broader use of cartoons and posters in activism like Sharad Sharma’s workshops, informed your approach to your environmental debut, River of Stories in 1994?

No. In fact, you ought to ask Joe Sacco the reverse question, because his Palestine (which as far as I’m aware was his first major work of cartoon journalism) came out several years after River of Stories! Same with Sharad Sharma. haha, just kidding.

What reception and effect did River of Stories have on the controversial Sardar Sarovar dam? Was it released only in English? Is it being brought back into print (its message is surely as relevant as ever)?

I doubt if the decision makers who went against the tremendous waves of protest and criticism of the Sardar Sarover dam cared to read my comics. But River of Stories did help in spreading the message of the environmental movement to a whole new audience of urban school and university audiences that were unaware of the impact such large scale development projects were having on communities, lands and resources. I still meet people who tell me they read River of Stories years ago and it helped change the way they looked at things like development and the rights of indigenous people in India. It was translated into Hindi and distributed in small photocopied batches amongst activists too. Yes I plan to re-publish River of Stories next year, for its continuing relevance, as you point out, and also for its value as a visual document of an important moment in the history of the environmental movement in India.

Tell me about your other short-form comics you have made for various anthologies - including the new one First Hand.

Since River of Stories, I have done many short form comics and edited as well as contributed to anthologies.These include Telling Tales - a series of slice-of-life stories that appeared in the (now defunct) India Magazine between 1995 and ‘1997; Imung, a comics-based community healthcare manual for caregivers in Manipur in 1996; Trash, a children’s book on ragpicking and recycling in India in 1998; The Night of the Muhnochwa, a fictional take on a spate of alien sightings reported from rural Uttar Pradesh in 2003 for Outlook magazine in 2003; Scattered Rice based on Ramakrishna Paramhansa’s autobiographical narration of his first mystical experience as a child, for First City magazine in 2004; Visioncarnation, a fantasy fiction piece satirising new-age reincarnation theories, that appeared in the South African magazine Chimurenga in 2007; Scenes from the Zone, a graphic documentation of the life of an urban garbage dump near Delhi, for Himal magazine in 2010; two stories of The Plasmoids with writer Samit Basu, and Hair Burns Like Grass for Pao: the Anthology in 2012; The Adventures of P.R. Mazoomder, the first of a planned series spoofing masked superheros via the character of a middle-aged Indian masked superhero, in 2013; Making Faces, a graphic page-turning game/narrative for This Side, That Side: Restorying Partition, in 2013; Portrait of the Artist as Old Dog, a story about ageing, for Dogs! An Anthology in 2014 (above); and The Girl Not from Madras with journalist and writer Neha Dixit, a true story about human trafficking for First Hand; Graphic nonfiction from India earlier this year.

Are you planning another graphic novel of your own? I read you were planning a new graphic novel around the Dodo. Where did you get to with this?

Yes, there are two new projects that I have on my table, apart from plans to bring out an updated, colour version of River of Stories - all planned for 2017 and 2018. The Dodo story is one of them. But I’d rather not talk about them yet.

What are your views on the opportunities for Indian comics creators today, with the expansion of graphic novel makers and publishers, the arrival of large Comicons, etc?

To be honest, I don’t think Indian comics creators have come up with the quality or quantity of excellent work that is needed, yet. It’s not really about publishers and opportunities. It’s about the artists and writers. There’s a lot of promise and talent. But I don’t see the level of dedication and committed hard work that is required (so says the curmudgeonly old man of Indian comics - hehe!)

How did you come to make the 7-story, 75 metre long fibreglass and acrylic “walk-through mural experience” at the Virasat-e-Khalsa Museum in Anandpur Sahib? And what were your inspirations and ambitions for it?

This is too big a subject for me to write afresh about, but will try and find something I’ve written earlier.

What other collaborative projects have you taken part in? And have you created work specifically for galleries?

As I mentioned earlier, People Tree is like an ongoing collaborative project, where I work with other artists and craftspeople in diverse mediums from textiles to terracotta. From the past couple of years two projects worth mentioning in this context are Utopia Dystopia Go, executed through collaborative workshops in late 2014 (Here’s a video about it…: it’s rather long, so you can safely skip the first three minutes) and Tall Tales, an open-air installation featuring 6 supersized sculptures of literary characters from across the world, for the Jaipur Literature Festival in January this year (some photos here…). I travelled to Palestine in March/April this year, and created three collaboratively produced murals in public spaces, working with Palestinian children and British artist Tim Sanders.

Since 2013, I have also been working on an ongoing collaboration with students of Goa University entitled Mapping Mapusa Market, through which we have been investigating the life, craft and food cultures and history of one of Goa’s oldest marketplaces. More about it on this blog…

Though my work has been exhibited on various occasions, the only time I have created work specifically for a gallery show was in 2014. The show was called Imposters, and consisted of screen-printed posters that parodied, as well as paid homage to, iconic pop culture figures, posters and graphics of the ‘60s and ‘70s. It showed at GallerySke in Bangalore…

Tate Modern here in London is showing Bhupen Khakar’s work. How do Indian fine artists like him, or others past and present, inform your work?

Bhupen Khakar was one of India’s seminal artists in the ‘80s, when I was a student of design. As such, I was influenced by his work, along with that of others like K.G.Subramanyan, Vivan Sundaram, Nasreen Mohamedi, Arpita Singh and others. The thing I love about comics, though is that it brings together elements of several arts - not just painting, but cinema and literature too. I was equally inspired by the work of film makers and photographers such as Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen, Ritwik Ghatak, Raghu Rai, Pablo Bartholomew and others who were all active in the ‘70s and ‘80s. I was never too much of a reader of literature somehow, and preferred to read non-fiction of various kinds. An exception - that I found very inspiring - was Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children.

And more broadly, what roles do feel the long and rich traditions of narrative arts in India can play in your own work and in the modern developments of distinctly Indian graphic novels?

I don’t strive personally to seek out an ‘Indian’ style. My work comes out of a life lived in contemporary India, and engages with the histories, geographies, social cultures and politics that I am steeped in. That is what is primarily modern as well as Indian about my work, As for India’s artistic and narrative traditions, I do absorb them, but do not try to consciously stylize my work. That would be superficial and dishonest. The only time I’ve created work that emerged from a deliberate study of Indian art was the visual style that I came up with for the mural at the Virasat-e-Khalsa museum. I deeply studied miniature painting styles from the erstwhile Punjab hills (Chamba, Basohli, Kangra, Guler), and borrowed aspects from their perspectives, compositional structures and narrative devices. But I combined all this with elements from other sources of inspiration such as Pieter Bruegel, modern comics, and also popular Indian commercial art.

Is it fair to say that graphic novel and ‘serious’ comics such as yours remain quite marginal in India, often available only in English and at a fairly high price? What would you like to see done to broaden their readership and appreciation?

Most kinds of art are marginal. period! Anywhere in the world today, there are very few forms or genres that have a broad, universal appeal - be it in music, cinema, literature or art. If we were to look at the UK, for example, where everyone speaks, reads and writes a common language, you still would be hard put to find one artist or writer or musician whose work almost everyone would be familiar with. In a hugely diverse country like India, perhaps only mainstream Bollywood films can claim that kind of popularity. So I don’t think we should expect comics to reach out and become popular across languages, communities and classes of audiences. Having said that, I agree that language is a very big problem - not just for readers but for creators as well. I create characters who speak in various languages, dialects and styles in my head. But when I have to put their words down on paper, they get all flattened into one rather boring standard English! I have been experimenting with multi-lingual as well as silent comics as a way of getting around this problem - but they both have their limitations obviously. I envy cinema for this one reason - for its ability to retain the sounds and flavours of languages! Perhaps online comics can offer solutions, with devices that are not clunky and self-defeating? I look forward to collaborating with some techies on this one day!

=====

In 2019, Orijit Sen kindly asked me to write a foreword for a new edition of River of Stories. This was eventually published in November 2022 by Blaft Books, with both my foreword and another by Arundhati Roy.

Foreword by Paul Gravett

Like the many tributaries that feed into one river, but retain their own sources and wellsprings, there are also many Indias combining to make a diverse, dynamic nation. That plurality is a strength that needs to be sustained, but not everyone accepts its advantage, and in fact its necessity. In the 21st-century acronym BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India and China), India was predicted to provide the vital vowel ‘I’ , and rise up as one of the four nations that would reshape the global economy in the new millennium. In the headlong rush towards modernisation and homogenisation, progress was unquestioned and positioned as a national duty, no matter what might be destroyed and who might be abandoned. And that includes the so-called ‘backward people’ living on the land of their ancestors, who want to retain their way of life and their belief in deities and spirits held over many centuries. But they are faced with displacement by a massive dam which will flood their homelands. ’Progress’ may bring benefits, but at what price? It seems inexorable and like the sirens of Greek myth, people cannot all ignore ‘…the sirens of the factory… calling, beckoning…’ them to move to the big city.

But hopefully people can also hear the songs and wisdom of legendary singer Malgu gayan. His stories of creation and other myths are presented here in richly toned and textured artwork, made more nuanced and tactile in a palette of greys. The page layouts become more open and flexible, more natural and flowing like a river, in contrast to the tighter grid of rows of panels for the present-day, realistic documentary parts of the book. Orijit Sen contrasts these contemporary scenes by drawing them entirely in pen and black ink, arriving at a fusion between Hergé’s crisp Clear Line contours in Tintin and Crumb’s gritty, detailed feathering and hatching, like a British engraved print by William Hogarth or James Gillray.

These two worlds and times collide in a telling wordless panel where the singer sits, unnoticed, atop a cliff looking down at the bus driving below, taking Vishnu the reporter and Anand the activist to a protest rally. Finally, Malgu gayan enters our contemporary world and his song rings out across the valley, and across the gutter of the wide, open valley of the double-page spread. Boldly, Orijit Sen inserts the actual two-page report published in The Voice, and follows this with the kaleidoscope of debate. After the divisive reactions and opinions, the singer fittingly returns in an epilogue that distils his wisdom.

Comics are narratives in fixed images. Their fixity cannot be overstated. In our present ‘attention economy’, in our endless torrent of fast-breaking news coverage, a significant story can come to us live, moment-by-moment, but often in an instant it is gone, replaced, often forgotten, by the next story, and the next… Like a River of Stories. The images and words in printed comics, however, do not go away. You can’t swipe or scroll them out of sight and switch to something else, you can’t click from them and jump to another report or website, you can’t change channels. This is a real strength of the medium. These stories, these voices, these ideas, these questions persist - and they resist, and they insist. Orijit Sen’s landmark work of graphic reportage is all the stronger for being in comics form, because he has fixed these events and ideas into drawings and texts printed onto paper, for more and more people to learn from. Twenty-five years later and more urgent than ever, they continue to flow with us into the future.

Posted: August 16, 2017The opening Article originally appeared in ArtReview Asia Magazine.